How Muslim Hands is combatting water shortages in one of the worlds poorest countries

‘We need water! When will you help us?’ These are the desperate cries of Abida. ‘The situation in this camp is a disaster! We would rather die than live like this’ another woman echoed. Internally displaced at an isolated camp in the desert city of Ma’rib, Abida’s home is now a tarpaulin cloth supported by a pole, which barely protects the family of seven, from the unbearable forty-degree heat. At this point she had no access to water for five days. Stories like these in Yemen are appallingly widespread. Already a water- scarce region, the civil war has exacerbated the situation, and ten years on over fifty percent of the population are struggling to buy and find enough clean drinking water to sustain themselves and their families each day - UN.

The ongoing conflict has severely damaged crucial safe water sources, which will cost millions to rehabilitate. With an already outdated infrastructure going back to the British colonial era, urban areas such as Ma’rib and the capital Aden, were already struggling to supply piped drinking water directly to local homes. Fast forward to the present day, the population of these governates continues to surge, as those fleeing violence or leaving rural villages with water shortages, flood into the cities. In the last ten years, Ma’rib’s population has increased from 30,000 to a staggering 1.5 million people.

State-run water companies only provide to households that can afford the costs, and even then, the water service is only available four hours a day twice a week. In both urban and rural locations families are forced to try and find free water from public fountains and wells, such as those located in local mosques. Unfortunately, even the mosques are turning people away because they are unable to keep up with the increase in demand. Many also rely on trucked water bought at extortionate prices, dictated by the suppliers.

Muslim Hands visited a water truck point in Aden, home to over one million Yemenis. Hoards of women, children and men with their containers and donkeys in tow, take on the exhausting journey to the water truck every day. One man told our team that he has had no clean water in his home for two years. He said, ‘look how many people are here struggling just to get a drop of water! Many are ill and still must carry home water containers every day. Some days I can’t fetch water for my family because I faint on the way. The water scarcity has gotten worse in the last two years. Trying to find a reliable water source here is like digging for gold.’ With aid cuts and inflation, intervention is vital, if families in Yemen are to survive in this devastating landscape.

For decades, the Arab world’s poorest country has also grappled with the impact of climate change, with mass flooding, drought and outbreak of disease amongst the obvious signs. Ahmed, a farmer who lives in the mountains of Abyan is responsible for his family of nine. As sheep grazers, the arid lands where he lives means finding an adequate water source is extremely difficult. They are completely dependent on what they grow on the land for their sustenance and as the weather gets drier the crop quantity reduces. He told our teams, ‘Prior to the intervention of rehabilitating our local water well, we were often left with no water when we reached the well. When we did find water, my donkey found it hard to carry home because of the unsafe roads.’

Those that are most impacted by water scarcity in Yemen are women and children, who make up 80% of those in acute need and 75% of internally displaced people. Women dominate the domestic sphere as the main care givers and are responsible for how water impacts their household. They walk miles every day to fetch water that is often unsafe, making them and their children susceptible to diseases such as cholera. Women often prioritise their family’s water needs and therefore lack access to clean water to live comfortably.

Naima from Khokha is a mother of five in her thirties. Her husband tragically passed away from a mine explosion leaving her as the head of her household. She said, ‘I work by knitting palm leaves. Life is very tough, and I have a chronic illness. Me and my children walk for miles with our buckets and containers each day to get water from a well. I only have enough to give my children bread and tea. I am very ill, and I don’t know how I will continue to provide for my children.’

Muslim Hands’ first water project in Yemen was the rehabilitation of a water well in the village of Bir Al-Sheikh in Abyan. The poorly functioning well meant that thousands of IDP’s flocking to this area were going without sufficient water for weeks at a time. Because of this, families in the area, including Fadhel’s were worried that if intervention didn’t take place, unsafe drinking water as well as a poor sewage system would continue to spread the risk of disease. He said, ‘we were miserable because my mother was unable to cook and there was not enough water for our family of eight to wash and clean with. Now safe water is available for all the families in the village. We have seen an increase of people settling in the village because of this water point.’

Muslim Hands work in Yemen started in 2019 and the charity has spent over £19 million on various projects including bread bakeries producing tens of thousands of loaves each day to support the most vulnerable as well as medical facilities and schools. Over 3 million has been spent on twenty-five water projects across Yemen, which is supporting approximately 3.3 million with safe drinking water. Majority of the funds have come in during the Islamic month of Ramadan where Muslims donate their Sadaqah and Zakat to the most needy worldwide.

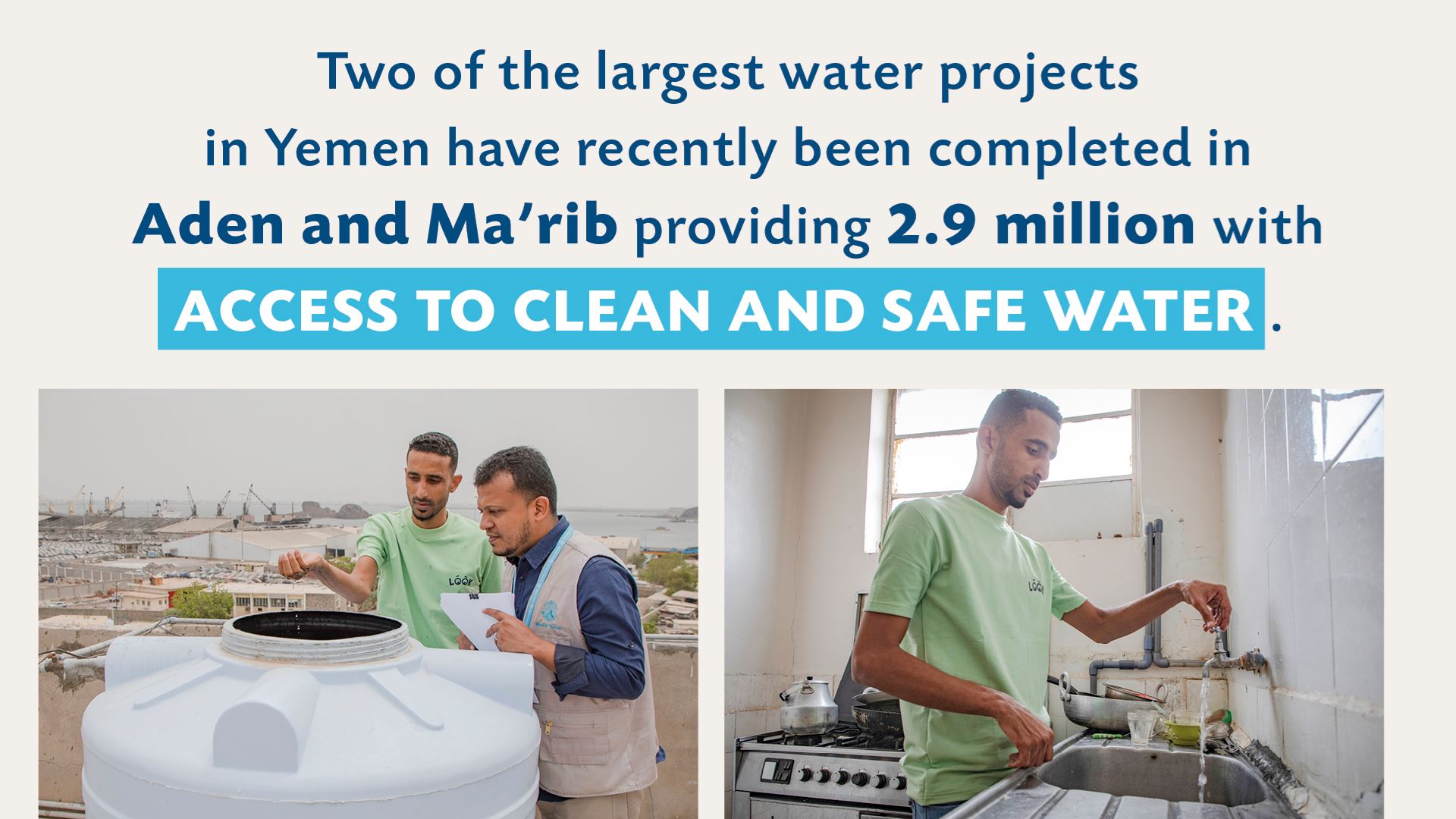

Two of the largest water projects by Muslim Hands have now been completed, initially in Aden and Lahj in 2022 and now in Ma’rib, which was inaugurated in August 2024. The aim for both these projects was to rehabilitate the existing water system to increase water production and improve the water supply to support a collective 2.9 million people – majority of which are women and children. Other projects include restoring deep water wells, installing solar panelling and building new sustainable distribution points, making safe water easily accessible to all.

Yasrab Shah, Fundraising Director at Muslim Hands was part of the inauguration process of both water wells and said, ‘it was overwhelming to be part of the recent inauguration of the Ma’rib water project because it will make a huge difference. A beautiful response was a day after the inauguration, a local imam of one of the largest masjids in Ma’rib greeted us with such hospitality and displayed his gratitude for what Muslim Hands is doing in one of the fastest growing cities in Yemen. It shows how water projects like these are lifelines.’

Mufaddal who lives in Ma’rib echoed the same sentiment telling our teams, ‘We are wholeheartedly grateful to the donors who came forward to help us. This intervention has drastically improved the water quality and service we receive. Prior to this we would use water tankers at extortionate prices, which would take a lot of effort and time. Now we receive safe drinking water regularly in our homes and at minimal costs.’

As the ten-year conflict shows no signs of abating and climate change continues to impact land and lives, families in Yemen have no choice but to carry on, navigating some form of normalcy. Though their stories show sheer resilience, the harsh reality is that unless drastic intervention is taken by charities like Muslim Hands, millions in Yemen will fall deeper into what may eventually become a forgotten crisis. Put simply, water is life and access to safe water will mean the difference between life or death.